Fearing Digital Literacy September 8, 2008

Posted by Eyal Sivan in Self.Tags: atlantic, brin, britannica, carr, edge, google, kelly, literacy, mcluhan, new york times, shirky

trackback

![]() The July/August 2008 edition of the Atlantic magazine featured a very provocative cover story. Using the infamous colour scheme of the world’s most popular search engine, the headline asks: Is Google Making Us Stoopid? The article, written by IT pundit Nicholas Carr, argues that yes, in a sense, the Internet is making us stupid. The truth is, he’s just plain scared.

The July/August 2008 edition of the Atlantic magazine featured a very provocative cover story. Using the infamous colour scheme of the world’s most popular search engine, the headline asks: Is Google Making Us Stoopid? The article, written by IT pundit Nicholas Carr, argues that yes, in a sense, the Internet is making us stupid. The truth is, he’s just plain scared.

In the article, Carr clearly demonstrates an intimate and well-researched understanding of technology and media, and his conclusion is clear. The Internet, he claims, is “chipping away our capacity for concentration and contemplation,” serving to “scatter our attention and diffuse our concentration.” To be fair, he acknowledges that he may be wrong, stating that “you should be skeptical of [his] skepticism;” that we may be on the cusp of a “golden age of intellectual discovery and universal wisdom.”

After its publication, the article triggered a veritable barrage of opinions from amateurs and experts alike (mostly at Edge.org and the Britannica Blog). Some of the heavyweights agreed with Carr’s position, while others disagreed, all with varying degrees of passion, and all with appropriate eloquence and regard.

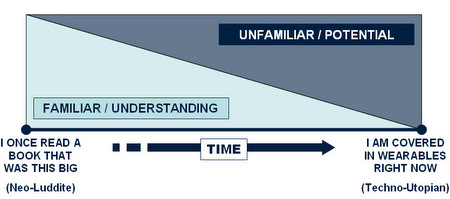

Summarizing and responding to each position would take far too long, so here is my analysis in the form of a simple diagram:

Please note that the above is a glib interpretation of the authors’ positions, and in no way mathematical, or accurately representative of their whole arguments. It is intended as a general (and hopefully humorous) summary. If anyone takes issue with their positioning, I would be happy to move them. The point is that the argument has been generally framed in terms of extremes.

With a nod to Carr’s article, the New York Times joined the fray on July 27 with an impressively neutral piece entitled Literacy Debate: Online, R U Really Reading? Early on, it clearly defines the extremes: critics of reading online say it “diminishes literacy, wrecking attention spans and destroying a precious common culture that exists only through the reading of books;” while proponents say “the Internet has created a new kind of reading, one that schools and society should not discount.”

The article goes on to mention international assessment tests for gauging children’s digital literacy, a fascinating term. Really, that’s what much of the debate seems to be about: whether digital literacy is a bad thing, eroding our ability to sustain deep thought, or a good thing, re-wiring our brains for the digital world ahead.

This post is not intended to argue for one side over the other, but to examine the heated and sometimes surprisingly fearful nature of the debate itself.

In searching for the aforementioned New York Times article, I accidentally came across another article that made a similar point, with one big difference: it was published well over one hundred years ago, on December 17, 1881. The following is a long quote (made possible by the outstanding archive facility at nytimes.com):

“It has been asserted that everybody nowadays is too much given to newspaper reading, and that there is imminent danger that book reading will fall into disuse… Still, book-making increases and book-sellers thrive. At the same time, and with greater rapidity than the number of book-buyers increases, the number of newspaper readers is multiplied. With education the newspaper reader demands constantly improving journals of information – fuller details about Governments, men and things – and with greater accuracy in detail than ever before. In answer to this demand the newspaper publisher must strain every nerve to supply the readers of his newspaper with the amplest and most trustworthy information obtainable, and that not only about events, but about the discoveries of scientific men, the results of exploration, the most recent thought in philosophy, the latest tendencies to Church and State, and even the argument in the latest opera or the cream of the latest novel.”

Now re-read the above paragraph, but replace newspaper with blog. What you’ll find is an almost perfect reconstruction of today’s best arguments in defense of digital literacy. Frankly, its disappointing that such self-evident truths need to be proven over and over again, that we are seemingly so incapable of learning from our past. Yet the same old and obvious arguments ensue.

Some of the arguments centre around absolute definitions of good reading and bad reading, but even elementary philosophy tells us this is a dead-end. Tolstoy may be wonderful for some (like Larry Sanger) and terribly boring for others (like Clay Shirky). The heart of the matter is that there is no one right answer. Tolstoy is not always great, and he is not always boring. Like all art (some would say like all knowledge), what Tolstoy is or isn’t is in the eye of the beholder, it’s subjective. If you prefer RSS feeds to War and Peace, go to it.

Other criticisms have to do with the immaturity of the tools, but this is simply a matter of time. Prior to blogs, wikis and podcasts (which was not so long ago), the Internet was not even especially good at engendering opinion, something even Carr’s supporters admit it excels at today. Eventually and inevitably, there will be ways to “let the pearls rise and the worst of the noxious toxins go away,” as David Brin desires in his excellent response.

There is no question that the Internet is changing how we think, but it is myopic in the extreme to label the result as stupidity. It also betrays an implicit fear of digital literacy.

Fear of new media is not unique to this age. Socrates feared the written word. Religious leaders feared the printing press. As the above quote demonstrates, literati of the day feared the newspaper. Today, the film, television, radio and music industries openly quake in the shadow of the Internet. From the original Luddites to the Unabomber, new technologies have often bred fear.

Some would say that the dissidents were right, that they were prescient in their warnings, as many of the technologies they feared have led to stratification, inequality, corruption and death. In every case, however, even with the blood on the wall, there was no turning back. Reverting, or even just stopping technological progress is contrary to our evolutionary, temporal nature. Technology marches forward because we march forward.

The concern should not be about technology per se, but about the damage it often causes. In my opinion, much of the suffering brought about by new technologies may well have been avoided if there had been more concerted and public efforts to understand its implications. These efforts must first and foremost work from the premise that there is no going back. As soon as one says, “No! We were better off without it, ” that’s just plain fear.

One answer to this perspective comes from Marshall McLuhan’s seminal Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, published in 1964:

“Literate man is not only numb and vague in the presence of file or photo, but he intensifies his ineptness by a defensive arrogance and condescension to ‘pop kulch’ and ‘mass entertainment.’ It was in this spirit of bulldog opacity that the Scholastic philosophers failed to meet the challenge of the printed book in the sixteenth century. The vested interest of acquired knowledge and conventional wisdom have always been bypassed and engulfed by new media.”

New media subsumes the old. It does not exist beside the old media, like a second option. It wraps around the old media, enveloping it, so that the new can do everything the old could do, but more. As a result, we tend to cast new media in roles we understand, so the Internet becomes a telephone and a radio and a television and of course, a book. The new media is always capable of much more than fulfilling these old roles. The problem lies in that we have no conception of what this more could possibly be, as we have no context for it yet.

Furthermore, this shift is inevitable. Technology does not go backwards, or as Clay Shirky puts it in his response: “the one strategy pretty much guaranteed not to improve anything is hoping that we’ll somehow turn the clock back. This will fail, while neither resuscitating the past nor improving the future.”

I think this inevitability scares some people. It is difficult for them to accept the validity of digital literacy, let alone imagining that it could completely subsume our immortal love of the written word. In order to deal with this fear, they hide behind McLuhan’s “bulldog opacity,” and trumpet the achievements of days long past, yearning for simpler times while simultaneously riding the current of their age.

The debate is not about smart versus stupid, or contemplative versus scattered, or deep versus shallow, or long-form versus short-form, or screen versus page. It is about us conceding that there is new way on the horizon, which is neither better nor worse, but new. This new way threatens the old way, a way which we may know and understand, which allows us to form nicely-bounded definitions of stupid and smart, but a way which must evolve all the same.

The diagram below illustrates this point. As time moves forward and technology develops, what the two end-points represent will change, and we most certainly can and should direct that change, but the battle between the familiar and the unfamiliar is never-ending:

Time is against us, always and unyielding. We can either turn our backs and pretend this new way isn’t coming, or we can face it head on and try and understand what it means for us, what it says about us.

Deep contemplative thinking is not necessarily the absolute best way to think. Nor is thin-slicing an absolute good. But the former is a well worn path, with many established and revered landmarks, while the latter is wild jungle waiting to be explored.

We cannot afford to be afraid, for it is that very fear that will lead to the dumbing-down of society for which all sides share concern. Google may or may not make you stupid by today’s definition, but not Googling will almost definitely make you stupid by tomorrow’s definition.

Kevin Kelly, in one of his responses to Carr, put it beautifully:

“We are about to make the next big switch. Billions of people on earth will stampede to join. Something will certainly be lost. It would serve us all better if that lost was better defined, and it was paired with a better defined sense of what we gain.”

Fear of the unknown is a peculiar but common condition. We have all been in some situation facing the precipice at the edge of the familiar, hearts beating faster, mouths dry. We experience this fear as a society too: fear of terrorism, fear of immigration, fear of gay marriage. All these can induce fear because they represent the great unknown. The Internet is no exception.

Faced with such a challenge, it must be remembered that this is neither the first nor the last time our global culture will suffer from the peculiar plight that is the fear of the unknown. Although the context is very different, the immortal words of Franklin Roosevelt seem strangely fitting:

“Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

It is grossly unfair to compare the cultural artifacts of the written word, which has ruled us for millenia, to the cultural artifacts of the digital world, which has existed for barely the blink of an eye.

Given time, digital literacy will give us so much more than the written word ever has, or ever could, for better or worse and whether you like it or not. We must learn to confront our fear, and convert retreat into advance.

Our future should not be shaped by the preservation of the old, but by the discovery of the new. Today, change is ever upon us. Rather than driving into the future using only our rearview mirror, as McLuhan observed, we should embrace our new tools, and strive to understand them as best we can, for the betterment of all of us and each one of us.

You write,

I’m not sure if you’ve read Kevin Kelly’s “Scan This Book!”, an essay from about two years ago. He writes,

It would be great if I could do what Kelly describes, if, while reading The Divine Comedy, I could follow links to Ulysses’ appearances in Virgil and in Homer, and to critical essays on Dante, on Virgil, on Homer, on James Joyce. What would not be great at all would be to forgot how to engage ideas in a serious way, to flit from shiny thought to shiny thought. Further, The Divine Comedy has value in and of itself.

This is not a technical problem, which is why I disagree with Carr. It’s not Google’s fault if we graze rather than engage in sustained discussion with great ideas; it’s our fault.

Where you and I do not agree, apparently, is that I believe deep contemplative thinking should be privileged, highly, above thin slicing. Not because it is always the best way to think about every subject all the time, but because it is often the best way, and because thin slicing is easier and more attractive.

Anxious,

First off, thanks for the Kelly link. I am big fan, and had not come across that one. I haven’t read Dante, but I can definitely sympathize with wanting to hyperlink my way across fiction. In a recent response to a Kelly post, I say that, for now, the Internet is not a very good storyteller.

To me the question about serious engagement of ideas is an ironic one because it strikes me that that is precisely what you and I are doing. Since I started this blog, I have engaged in more deep contemplative thinking than I ever have before. Because I choose what I want to think about, no-one chooses for me. And because its not just me and the books, its me and you and everyone else.

Think about it, which is more intellectually demanding? Having a panel of experts tell you which books are considered good enough to read, or having all the books in the world thrown at you, all sewn together with hyperlinks, and surrounded by never-ending conversations exploring their styles, themes and ideas. That’s why I use the word fear: to me (and to Carr), the second is a lot scarier. It also demands, in my opinion, a lot more of all kinds of thinking, deep and contemplative notwithstanding. We’re just not very good at it yet, and neither are our tools.

As far as whether deep thinking should be privileged: This is going to sound a little mystical, but I believe that at some core level, deep contemplative thinking and thin-slicing are the same thing. Zen Buddhism and Taoism both teach living in the moment, forgetting time. Even some Western philosophies conclude that there is nothing, or that time is an illusion. As Socrates said, “the only thing I know is that I know nothing.”

I don’t feel the internet has eroded deep reading or serious contemplation, but it has added an extra step.

With the dramatic increase in the amount of information available, the ability to filter, aggregate, and organize becoming required skills.

A sentiment that runs through much of McLuhan’s writings is the difference between the mechanical age and the electric age. In order to cope and transition, we need to see evolving skills as complementary rather than contrary.

Much of our socio-political infrastructure and conditioned behaviours are based on principles formed around the industrial revolution, and lack relevancy in this day and age where life is more simultaneous than sequential.

Filtering, aggregation and organizing are how we cope in a simultaneous world. It is how we decide what we read deeply, and allows for both greater specificity and a broader base of knowledge.

trev,

I completely agree. It’s all about balance. Well said.

No, it’s not about “fear”. That’s how you extremists always try to ridicule your opponents, attributing “fear” to them. I would have to agree with Nicholas Carr, that Google *does* dumb you down — first and foremost, for a reason Carr doesn’t mention, because it fetches up Wikipedia on that topic in the first slot of all the returns. It’s there because…it was there for the previous searcher, and they clicked on it, and linked it. It’s a self-fullfilling prophecy, and doesn’t really reflect “authority”. All you have to do to understand how that works is to look up “Edelman” the PR firm. They make sure through SEO that their own site shows up on a Google search, instead of Wikipedia’s entry. And both manipulations and mindless self-replications from clicking are contributing to making us stupid.

Yesterday I held a book that was a copy that was literally 100 years old in my hand and read it (“Of Human Bondage”). I wasn’t trying to push technology backwards. I was simply taking advantage of good technology’s persistence even in a context of destructive technology which you dub “disruptive”.

Catherine,

“You extremists?” Ouch. I’m not trying to ridicule anyone, and I’m not attributing fear to just my opponents. To the contrary, I’m scared too. The implications of our transition to connectives is overwhelming. The difference is I admit it, and try to see it for the scary process that it is. To just call it “dumb” or “stupid” and be done with it is avoiding the question entirely. That’s why I appreciate Birkerts position so much – he’s clearly worried and a little sad, but is exploring all the same.

Many of your other conerns (i.e. PageRank’s implicit groupthink) are shortcomings of the tools. Remember, these tools are young. They will get better (I hope).

Your book sounds wonderful. I love books. I love pen and paper even more. That doesn’t mean those technologies didn’t destroy their share of human faculties along the way.

Eyal, you’re shockingly extremist, and you need to accept the consequences of your speech. And ascribing “fear” to people who disagree with you or critique oppressive new technologies is indeed something you have to take ownership of. *Of course* you’re ridiculing people with your little line diagrams there — and guess what, there aren’t any wearables.

There aren’t any wearables. That’s something in Rainbow’s End, a *book* and a work of fiction.

You’re happy to have the dissidents’ blood on the wall, because they need to “accept reality”. Here you are suddenly lamenting that technologies “destroyed their share of human faculties” but in fact, in the end, you celebrate the destruction because you claim it is inevitable, and mandatory. You can’t turn back the clock. Billions will stampede, etc. You insist technological change is inevitable — and you privilege yourself as some sort of scientist that will a) get to make a judgement about this b) evade its effect on himself c) somehow force others to adapt.

It’s wrong.

The Internet does dumb people down, but it is not irreversible change, nor as stark as you portray it — it’s reversible, it’s controllable, and it’s not the case that there’s some charging Hegelian imperative here of “progress” that marches along leaving breakage in its wake that we “must” adapt to.

Books are still here. People don’t adapt — and that’s fine. There is nothing inherently “progress” about destructive technology — it is actually a profoundly conservative force in that it prevents the modern liberal faculties of freedom, democracy, equal participation, etc.

These concerns aren’t just because the tools are “young” — they have these awful features already welded into them. They aren’t getting better, but all the APIs and proliferation of services are making more disintegration and creating a vast and very weakened clientele for them which then makes the situation rife for one very big application, like Microsoft, simply to move in and remove all the annoyances. Lotus 123 was too hard to use and annoying to learn; Wordperfect wasn’t; pretty soon everybody used Word.

Someone once asked a Zen teacher to sum up Zen in a single word, and he said, “Attention.” Flitting from hyperlink to hyperlink is not (necessarily) paying attention. Zen trains our minds to do what is not always easy. That’s why it’s work. Deep contemplative thinking is hard; thin-slicing is (generally) easy.

Easy things are fine. I don’t spend all my time reading Dante; I watch 30 Rock, too. Sometimes I do this. I’m not arguing against the Internets; I’m arguing in favor of (as in Catherine Fitzpatrick’s example above) 100-year-old books, especially ones with Spinoza references in their titles.

Catherine,

I do believe technology marches inexorably forward, and that in the process it amputates some human faculties along the way. This seems to me self-evident, but I am open to contrary views (any links?). I also think technology is morally neutral, not inherently “destructive” or “oppressive.”

So we have a choice: we can either remain within the comfort zone of existing media which we understand, or we can explore the potential of the new media. The former approach, it seems to me, is rooted in fear of the unknown, while the latter requires courage. Trev said it very well in his comment above:

Finally, I do not “privilege myself as some sort of scientist.” This blog is intended to chart an exploration of ideas, that’s all. My “judgments” are not gospel, and I don’t want to “force others” to do or think anything.

One very big application? I think not. The “weakened clientele” you speak of are the same people actually authoring services, extending platforms and providing content. They are not weak at all. If they demand better tools then the tools will get better.

By the way, wearables do exist. Check out Steve Mann.

Anxious,

I knew that would get me into trouble. Your point about Zen being attention is well taken; I’ll have to give that some more thought.

For the record, when comparing it to Zen I’m more referring to the kind of thin-slicing that Gladwell talked about in Blink, like in exceptional athletes or cops under fire, rather than jumping between hyperlinks. The kind that requires deep expertise to accomplish, but when applied it is almost immediate. It feels like there’s some parallel there.

Genius cartoons, by the way. The one you linked to was very on point.

I have to stifle laughter at your notion that technology marches inexorably forward when the Xerox machine is always broken and the system is always “down”.

I explore new media, Eyal. I live in it — in SL. I’m all over it. But, I don’t believe in the theory around it and being embedded in it against our wills by coders.

What services are they offering? Widgets that enable me to bite someone in a play vampire game on Facebook?

Good for people to know.

Facinating post Eyal…I’m impressed by your knowledge of the subject…as well as your ability to articulate your thoughts in such an interesting manner=)

I agree that the age of digital literacy is here and it’s here to stay…but that doesn’t mean that it would oblitrate traditional literature…..just like the advent of television, didn’t eradicate the need or use of radio, in fact we have more radio stations now than ever….same way wikis and blogs can’t replace books…I’m an avid reader and to me a digital library is an extension of the traditional one.

Rashmi, thanks for the complements.

I like your description of the digital library as an extension of the traditional one, as it seems to emphasize continuity. I think it’s important in this debate not to perceive the new as a replacement of the old, but as an added layer. I don’t know for sure, but I would guess that empirical evidence supports your view that new media actually proliferates its predecessors rather than eradicating them.

. . . thought you might be interested in participating in our new “Multitasking: Boon or Bane?” forum, featuring posts and commentary this week by Maggie Jackson (author of Distracted: The Erosion of Attention and the Coming Dark Age) and by popular tech writers Howard Rheingold, Nick Carr, Heather Gold, and Michael Wesch:

Forum link: http://www.britannica.com/blogs/2009/12/multitasking-boon-or-bane-a-new-britannica-forum/

Comments welcome!

Barb Schreiber

The Britannica Blog

Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

[…] Fearing Digital Literacy […]